IoT security is a mess, but who’s to blame? The tech industry must improve security for the internet of things.

The internet of things is quickly becoming every cybercriminal’s wet dream, especially given the release of the Mirai botnet source code. The cause is shockingly insecure devices, but can shaming manufacturers avert the coming chaos?

Last year, Symantec released a damning report revealing security flaws in common IoT devices. Some, like not using SSL to communicate and not signing updates, are shot through with incompetence and hubris. The report also described basic flaws in some IoT web portals. It’s uneasy reading unless you’re building a botnet, in which case it’s pure gold.

No chain of trust in security for the internet of things

Many IoT devices call home for instructions and updates but don’t bother with chains of trust. Using ARP cache poisoning, an army of devices is yours to update with new firmware, and to then command.

So, how big is the coming IoT cyber-storm? According to Gartner, by 2020 there will be a staggering 13 billion IoT consumer items online. Driving this growth is a gold rush that will be worth $263bn to manufacturers by the end of the decade.

To put this into context, the recent 1Tb/s DDoS against French hosting provider OVH involved just 152,000 hacked devices. To borrow from Al Jolson, we ain’t seen nothin’ yet.

We could simply build stronger defences, such as Google’s Project Shield, but this does nothing to address the underlying problem: insecure products.

Defending against insecure things of the internet

Cybersecurity professionals increasingly spend excessive time and energy defending against those products. And apart from bad publicity, there seems to be little consequence for manufacturers.

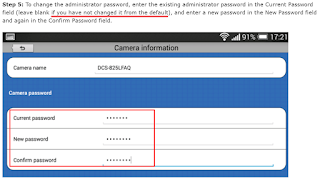

Ah, but surely responsible IoT companies provide updates as they become available? Well, yes. Up to a point.

Do your parents have any idea how to locate and install a firmware update from a support site? Mine neither. Why should they? They bought white goods, not a system administration course. By now, all IoT updates should just happen automatically, using a chain of trust that begins with code locked securely into the CPU and ends via client and server identity verification with cryptographically signed firmware images.

Online safety is at the heart of the problem. Consumers have a right to safe goods. IoT manufacturers have a responsibility to prevent their products harming others online. Do baby monitors that can be accessed by anyone sound safe to you?

The lamps in your lounge won’t randomly explode and set the curtains on fire. They meet legally enforceable standards. But a smart lightbulb can be hacked. We live in a changed world, and mere lightbulbs serving ransomware is becoming possible.

It’s not as if good IoT security is difficult to implement. Because of this, there’s an obvious and urgent need to enforce legal cyber-safety standards against manufacturers. One potential and very detailed testing methodology comes from the OWASP Internet of Things Project.

Condition of sale

My modest proposal is that IoT manufacturers be made to implement strong security in their products in order to offer them for sale. For this, we need independent testing bodies. Those products that fail would be denied a safety certificate, just like any other consumer item. Foreign imports would be subject to trading standards examination, with sellers facing prosecution for selling insecure goods just as they do for selling fakes.

Maybe then, as older devices fail and are replaced, will the IoT will slowly revert to the consumer paradise it was meant to be. If we have security for the internet of things we have security in the most immediate parts of our lives.

All posts

All posts